전시

-

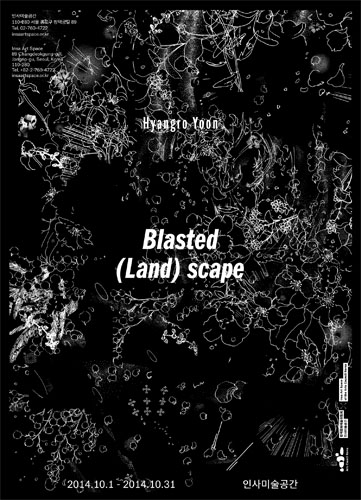

윤향로 개인전_Blasted (Land) scape

윤향로 개인전_Blasted (Land) scape- 전시기간

- 2014.10.01~2014.10.31

- 관람료

- 오프닝

- 2014.10.1 - 10.31 매주 (월) 휴관

- 장소

- 작가

- 부대행사

- 주관

- 주최

- 문의

윤향로 개인전_Blasted (Land) scape

2014.10.01 - 2014.10.31

ENGLISH

DIALOG

PHOTO

윤향로 개인전

Yoon Hyangro

2014.10.1 - 10.31 매주 (월) 휴관

윤향로는 이번 전시에서 대중만화의 도식적 도구들을 빌려와 실험으로써의 "풍경화"를 모색한다. 풍경을 구성하기 위해 활용되는 요소들은 내러티브의 극적 서스펜스나 심리적 정황 또는 인물의 모션 등을 예상하게 하기 위해 덧붙는 클리셰와 같은 장치들로 스파크, 동작선 등이다. 이러한 선들을 옮겨오는 과정에서 작가는 캐릭터와 대사를 지운 후 주변 공간의 흔적들을 선과 이미지 크기의 비율, 위치 값 그대로 가져온다. 다시 말해 작업에 얹혀진 원소로서의 이미지들은 선들이 아니라 주체가 지워진 상황 그대로의 레이어(Layer)인 것이다. 이렇게 추출된 켜를차곡 차곡 쌓고 배치하는 수행을 통해 산수화와 같은 이미지를 만든다.

작가의 최근 작업에서 사용되는 만화의 효과선(혹은 인터넷의 짤방_인터넷 게시판 유저들이 드라마나 뮤직비디오,영화의 주요장면을 캡처해 만든 움직이는 짧은 동영상 파일)들은 결과적으로 남게 된 작업 표면에서는 정보집적의 과정이 (잘)설명되기 어렵다. 수 천, 수 만 장의 만화 지면을 스캔하고 다시 모니터 상에서 필요한 선들을 가려낸다는 것은 물감과 같은 매제와 붓질의 여러 혼합단계의 과정과 비견될 수 있지만 윤향로의 매체는 물성으로의 그것이라기 보다는 데이터로서의 비물질과 결합한 회화이므로 이것이 어떻게 다른 차원으로 확장될 수 있는가 하는 문제를 전시장에서 마주하게 된다. (만화가가) 손으로 그린 이미지, (윤향로가) 눈으로 그린 이미지의 차이, 물직적인 것과 비물질적인 것의 교환, 주체와 배경의 왕복 속에서 회화는 어떻게 다른 차원의 요소와 결합할 수 있는가.

▲인사미술공간 지층 설치전경

전시의 전반적인 가이드로써의 인미공 1층은 도라에몽, 드래곤볼, 은하철도 999, 카드캡터 사쿠라, 슬램덩크, 베르사유 궁전 등 총 일곱 챕터 별 주체, 배경, 대사가 지워진 풍경들을 담은 책을 보기 위한 라운지로 변모한다. 단순화된 알파벳 기호와 여러 개의 넘버링, 산업적인 인덱스와 같은 제목의 작품들은 디자이너 홍은주, 김형재와의 협업을 통해

BLASTED (LAND) SCAPE, 책, 165x240mm, 2014

한편 작가는 이전에도 작품 안의 맥락과 전시장의 상황을 활용하여 관객과의 리액션을 염두에 둔 설치작업을 지속적으로 소개한 바 있는데, 본 전시

▲인사미술공간 2층 설치전경

옮겨진 풍경, 번역-이본(異本)된 형식적 풍경은 직관적으로 "바라보는" 풍경과 달리 많은 레이어를 추출해내야 하는 정보편집의 전후 과정으로 인해 시간적 공간적 매커니즘의 수많은 선택을 담보한다. 전체와 부분, 파편과 총체, 분해와 재구성, 디테일과 복원된 일체성, 순환으로의 회화는 이미지와 데이터로 둘러싸인 환경에서의 또 다른 회화‘언어’의 생성을 실험한다.

Imagine yourself standing in front of Hyangro Yoon’s works in her solo exhibition Blasted (Land) scape (Insa Art Space, October 1, 2014-October 31, 2014). Yes, you are in the exhibition space in the little basement floor of Insa Art Center, away from the bustling and narrow passage full of cars heading towards and moving out from the busy city center of Seoul. You must have walked past the old walls of Changdeokgung (palace) and entered the building through the hinged, rather big transparent glass door. Then you encountered the books, or, the copies of a book on the ground floor. You must have gone through the books before coming down to the basement. You might have picked up some images from upstairs already, which are now hung in front of you in scales ranging from 1:1(100%) to 1:6(600%) of the originals.

Images of the ‘blasted (land) scape.’ With enigmatic or cryptographic titles such as GE91-3,729, A-SS1-136, and S23-1,376, the images present assortments of certain features that look somewhat familiar yet strange and bizarre as well: you see some dots on sheets of paper; you witness lines that resemble some kind of contours; traces of quick movements; explosions; fluids of an unidentifiable kind; bubbles; currents of water; mysterious markings that share certain visual signatures; figures that might be flowers; what looks like a representation of the flow of air; flow of emotion, or something else. Whatever the origin of the images is or through whichever way they are produced, they are there with material presence: Printed and framed, they are hung on the walls of the exhibition space.

A step closer to the images, you try to figure out what is happening. In front of your eyes are apparently identical images. The only visible difference among the images is the size, which seems to follow a set order that can be possibly described as a regulated enlargement or blow-up. Other than the size, they look exactly the same, which makes you think that there must be something in this discernible identicalness. Time is ripe for throwing questions, then. Where did they come from? Do they represent anything? Is there any art historical reference taken by the artist? Above all, how are these images produced?

The answer for the first question might be found on the first floor where 2,652 ‘blasted’ images are shown in sequence via a two-channel video presentation. And you might have also guessed the origin of the images in the codified titles and the visual characteristics of the works. The images are originally from a series of Japanese manga titles that have been heavily circulated in Japan and Korea. About the second question, the issue of representation shall be discovered in the inner workings of you the viewer after you go through all three floors of the exhibition. The title of the exhibition can be a little hint in reflecting on the second question. In regard to the art historical reference, some might find the intended absence of the agents of actions in Yoon’s assortment of expressive gestures is similar to the notion of empty space in the Oriental paintings; others would sense that Yoon’s works share some visual characteristics of particular styles of Oriental paintings; given that the source material for Yoon’s works is Japanese manga titles, one might even consider that the artist is following a certain line of artists that work with a web of references that fall under the category of subculture.

Yet, what hits the retinae of you the viewer is not these simple speculations on the nature of the works. It is the unexpected identicalness of the images and their indiscernible fineness that shapes the experience of Yoon’s works in Blasted (Land) scape, which is deeply embedded in how they are processed and produced. In a way, it is the nature of the works that is present in a form of materiality. To examine it, one has to follow the passage through which the framed images in the exhibition space are produced, which involves a series of electrical charges, vaporization, injection and burst of chemicals, small-scale explosions, etc: The dots and lines on the sheets of paper in front of you are not the ones created by the very skillful hands of the artist but printed by a specific thermal inkjet printer that boasts a stunning 2,400 x 1,200 dpi(dots per inch) resolution and has an expansion package that enables the machine to adapt to the industry-standard image processing algorithm, along with a guaranteed durability of its prints up to 200 years.

Indeed, the whole series of works could not be conceived and materialized had it not been for the help of various imaging and printing devices, both in physical and non-physical terms. The dots and lines in Yoon’s works must have been initially a droplet of ink run from the tip of a pen held by one of the manga masters or someone at the production studios. After they had been created by hand at first, they were scanned and processed to be prepared for print publication. Once published in Japan, they were then brought to Korean publishers that rescanned them to substitute the original Japanese text with the translated Korean text. Either through a digital editing or through an analog cutting and pasting, the Korean versions of the original mangas were came into existence, which were then fed into printing machines that possibly used the offset printing technology, a technology that requires four different negatives to be produced before a set of paper is printed. The artist then scanned the Korean version of the mangas using a scanner equipped with the Digital Image Correction and Enhancement technology, feeding the resulting scanned images into Adobe Photoshop and InDesign to blast certain parts of the digital copies of the edited versions of the originals. For the publication for the exhibition, which is on display in the exhibition space on the ground floor, the artist had to send the processed images to the designers so that the whole series of works could be reproduced in the form of a publication, which is ironically done through offset printing. The color K of CMYK and another color element were used to make the color black look more thick on paper.

For the works in the basement floor, the final stage before they were detained in frames or the first stage of re-materialization after the whole process of scanning, blasting, and editing was the thermal inkjet printing in which the digital originals of the processed images were fed into a highly efficient printing machine. At the small nozzles attached to the printheads, the very dynamic and dangerous process involving small-scale explosions and the resulting burst of extremely small ink bubbles happened more than many thousand times at every single second while the images were being printed. Since the density of the highly controlled ink bubbles put on paper exceeds 1,200 dpi, your eyes cannot distinguish the difference between the identical images in different scales in the exhibition, under the condition that the digital originals of the images are also processed in a resolution setting beyond 1,200 dpi. Now, a mechanical error or some unknown technical failure might have created a glitch in this perfect circulation of images. Maybe it is the surface of the paper, which seems to be dead flat in our human eyes, that has generated some random variations. Or, it would be that flat empty space surrounded by the fine reproduction of the processed and blasted images where the true glitches, variations, or errors of reading what the artist calls landscape with parentheses lie.

Jaeyong Park

첨부파일